Photography Ralph Whitehead

Styling Giulio Cascini

Make Up and Hair Jade Soar

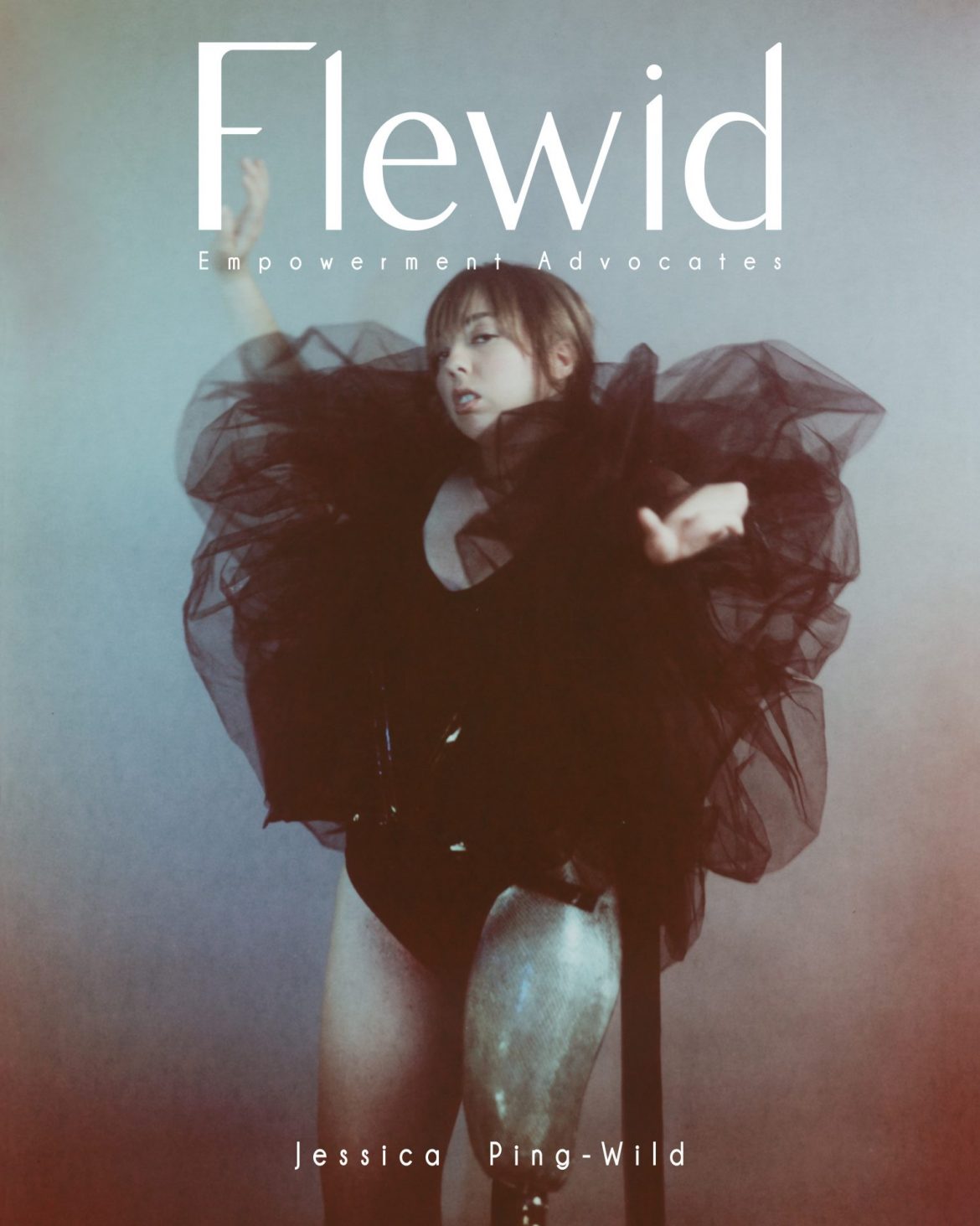

DIGITAL COVER STORY

Jessica Ping-Wild wears black tulle bodysuit Ilaria Lepore

Interview Johanna Urbančik

“I only have one leg and I could probably beat you in a dance off”, says Jessica Ping-Wild about herself on her acclaimed blog’s About Me page, and she’s probably right. Looking at Jessica’s Instagram and TikTok accounts, you see a bubbly, always happy-looking woman jumping and dancing around London educating her followers on disability and accessibility. The American blogger has made a name for herself through her lifestyle blog, The Rolling Explorer, where she documents personal stories and shares experiences – both positive and negative – from her life with CHILD Syndrome. Everyone knows that social media is curated and the perfect lives are sometimes only perfect on screen. With Jessica’s social media channel being so uplifting, empowering and motivational, Flewid asked her about what happens when she’s not having a great day. Read the conversation about social media, accessibility in London and why the conversation around diversity doesn’t seem to automatically include disabled people below.

Looking through your socials and your blog, you seem to be doing a bit of everything ranging from blogger to model and speaker to actor. Can you tell me how you got into those professions? Honestly, I look at it sometimes, and I’m thinking, why am I doing all these things? (laughs) But, I attribute it all to starting with a blog and writing. I studied English Literature at the University of Notre Dame in the US, and to me, writing was my biggest passion to this day, it remains something that I love to do so much. I don’t know if it’s still my biggest passion, but it makes me feel very joyful. After graduating, I started this blog because my mentor said it would help me become a storyteller and stand out in job interviews against any competition. I started the blog while working at my Alma Mater and relaunched it in 2020 during the pandemic. I also studied digital marketing a little bit in school and did some internships in that area. I knew the best way to get viewers on my blog was to advertise it on social media. That’s how social media really became a focus of mine. Then when reels came about, and TikTok was growing, I decided to start doing videos. It all snowballed from there.

What direction did you want to go with the blog, and is it still similar content to your original vision? The blog I am doing now is more focused on me, my personal brand, and who I am. I never saw it originally going that way when I started it, because the original plan was for it to simply be a way for me to progress my writing career. So at the time, I was looking at it being more of a travel blog, telling stories of my travels as a disabled woman. Hence The Rolling Explorer – an accessible travel blog.Of course, I would have been present in that, as it would’ve been written from my perspective. Whereas now, the blog now has developed into something that’s more about me and my life.

Is it scary to put so much of yourself out there? Terrifying. And I think people think they know me, they think I’m always happy. “Oh, you’re so positive”, “Oh, you’re so happy”, I get that all the time. They don’t see me at the times I’m in a ball crying on the floor because of any reason. They don’t see me every moment of the day, and I think that’s a confusing thing still in our world. Social media makes it feel like you do see everything.

What do you do social media wise when you feel like that? Do you still post motivational content regardless of you not feeling 100%? Honestly, if I’m going through a big rough patch, that usually is a tough one. I want to say this, if I am struggling mentally, I will probably not post on social media for a couple of days. I will probably be very honest about it in my stories. My Instagram stories in particular are where I open up a little bit more, whereas on my feed, I am very motivational. If I’m not feeling that way, it might not go up that day. I kind of learned to deal with that. Another thing that helps massively is I batch film my content. Therefore, I don’t have to film something every single day.

I want to go back to you putting yourself out there that much. What kind of feedback are you getting? I find there’s not that many blogs by disabled women, and in general, there aren’t that many disabled women that put themselves out there that much that are widely known in the mainstream. What resonance and feedback do you get from your fans and readers? I was a little worried about it first. My parents were as well. They asked me if I really wanted to talk about negative things I’m experiencing and put that out into the world? Because as much as my page is about motivation, it is also about being honest and sharing my experiences as they occur. They were worried I would struggle and get a lot of negative feedback, because I wasn’t showing up as the positive disabled woman all the time. And, I also don’t want to just be the positive disabled woman. It’s really important to showcase that, yes there is a time and place to be positive and motivational, but there’s also a time and place to be honest and authentic. Both of those things exist on my page. Having both of those things is scary to me, but it’s also empowering because it means I can tell my story. I can create my narrative and show up as myself all the time.

I want to talk about one of your blog posts about London Fashion Week. You write: “They told me that they were so excited to have me there to help model their adaptive fashion line. With that one word, I understood my role for the day.” How would you categorise the progress in the industry when it comes to diversity as a whole? Diversity as a whole, I think, is improving every single day. I think diversity including disabled people is still massively, massively too slow.

Do you feel that disabled people are included in the diversity conversation? There’s a big focus on sexuality, ethnicity, gender, etc., but I find disabled people are never automatically included in that conversation, especially in the creative industries. 100%. I think it’s not even just the media and entertainment industries I reside in. It’s every industry. A lot of the blog posts I write are for my page and other people’s pages. There’s so much data out there for diversity for women, people of colour, and even now LGBTQ+ individuals. There’s so much information out there, and people are studying that, which is great. But, it is so hard to find credible information when it comes to disabilities, how much representation they’re getting in not just media, but across the board and medicine, politics and all of that. It is so hard to get facts and have studies to back that up, which is frustrating because it’s just a physical representation of how little representation we’re getting. It showcases that not only are we not being thought about for these roles for these opportunities, but we’re not even being thought about to be worthy. We’re not even being thought worthy enough of fixing it or to create a conversation about.

Why do you think that is? I think there are several reasons for it. From a US perspective, the ADA, the Americans with Disabilities Act, was passed in 1990, and it was huge. It was the first national legislation for disabled people around the world, which was massive for the disability community. But with that, a lot of Americans think because the ADEA exists, the disability issue is taken care of, that’s it. That’s not good enough! Things are continuously changing. 15% of the world’s population is disabled. That’s a straightforward fact, and yet, so little is being done for that community. I think another thing is the narrative that’s been pushed in the media for so long is that disabled people are either one of two things. They’re either the motivational person that’s positive and can overcome their disability, or they’re lazy, kind of rude, not fun to be around and not willing to live their life because their disability is holding them back. In that respect, there are two categories: There’s one that pushes through and overcomes, and there’s one that just lets their disability run their life. That does not give view to the fact that it’s society that holds back most disabled people, myself included. Whenever I can’t do something, which is usually 95% of the time, it’s not because of anything being wrong with me, it’s because there’s no ramp. It’s because somebody discriminated against me. That’s a really big distinction.

You live in London, which is not the most accessible city. How do you cope in a city like that? One thing that really helps me is I live really central. The more central you live, the closer you are to touristy areas – and I say this all the time – but tourist areas tend to be more accessible because they have to cater to loads of different people either with strollers, buggies or prams and also wheelchairs. Living centrally has helped me get around. That said, I run into barriers all the time. I am constantly driving in the street. That is something that I really get angry about because it’s so unsafe, but I like constantly having to go in the road in order to get around because either the sidewalk doesn’t have a cut curb, or there’s construction going on, and they haven’t put a temporary ramp up. There are so many barriers. The tube, for example, is a nightmare. Less than half of the tube stations are actually accessible, of which most are in the centre. It already costs so much extra to be disabled in our society. People always say you can take the bus. They’re not accessible. Just straight up, they’re not. Then they say I can take a cab. So, I have to pay a minimum of 15 pounds anytime I want to leave the house. That’s not fair. You’re right. London’s not accessible, but I will say this, it’s more accessible than many other European cities I’ve been to.

I saw a Tweet on my timeline last week that summarises what you just said, Haraldur Thorleifsson writes: “A tourist asked me recently why there were so many people in wheelchairs in Reykjavik. I told him his country had them too, but it wasn’t as accessible so they stay at home. Same applies to all minorities. If you don’t see them it’s because they are hiding.”

You talk a lot about the pandemic and your anxieties regarding Covid on your blog as well. Do you think that the pandemic has made the way people look at people with visible or invisible disabilities worse? The conversation is so often “they should just stay at home. I want to live my life.”

You answered the question essentially. Yes, that is what people’s mentalities have been during this whole pandemic. It’s been exhausting to try to convince people that I, or my friends, deserve to live. I’m not personally immunocompromised, but that also doesn’t mean I’m not more susceptible to negative outcomes from the virus. It just means that my chances of picking up the virus aren’t as high as somebody that doesn’t have a strong immune system. It has been exhausting especially during the first nine months of the pandemic. I was tense every single day. I remember waking up angry, because I knew I was going to have to deal with seeing those sorts of comments on the internet. There was a lot going on politically at that time as well. I mean, I was stuck over in the US during that first bit of the pandemic. And there was clearly a lot going on, not just with the virus but also with the presidential election, which also led to a lot of tension. The pandemic showed me how much work still needs to be done to get people to care about disability. It goes back to your question about why disabled people are not being included in so many different things. It’s because people have these attitudes. They say “well, you’re disabled, you can’t contribute as much to society. Therefore, you’re not as important.” Also, a lot of people think we’re faking our disabilities. I get told my disability is fake, even though it is clearly visible. It is clearly not something that I could make up.

That’s ridiculous. How do you deal with those comments? It depends on the context in which they are commenting on. I think for me, if they’re telling me I’m faking it, I almost always laugh them off because that’s just so ridiculous. But if they’re commenting on something I’ve said, arguing about a point I’ve made about the disability community or telling me that I should just take a cab if I’m complaining about the tube or something like that. Those tend to affect me more because I think you’ve clearly not paid attention to the video, you clearly did not listen to what I was saying. And in some ways, I think those frustrate me more because why am I doing what I’m doing if it’s not sinking into the people that need it?

Flewid: What does the online disability community look like? I think it depends on who you ask. In some ways, it’s really tight knit. I think a lot of us want that representation because we want so badly to have our voices heard. We do rally around and behind one another. I’ve gotten really close with a lot of other UK disabled creators in the last six months in particular. I’ve really started to make those connections and even met some of these amazing people that are doing things similar to myself, which in itself is really powerful. There are parts of the internet though that’s not supportive, and people within the disability community that still have a lot of internalised ableism clearly to deal with. There’s a lot of work to do within the community itself. I always say my videos are not just for the disability community, they’re for non-disabled people as well. It’s for both parties, because both parties still have things to learn. I still have things to learn. And I think that’s also important to say and be ready to admit. For years, I thought so little about myself because that’s the way society wanted me to think about myself. I internalised that and brought that onto myself, and it’s just not healthy, not good for getting the message out there. It’s not good for changing the world in a way that’s more inclusive, but it is just the reality that there is more work for me to do. There’s more work for every person to do, disabled or not.